Just a few months before the end of World War II, the submarine USS Seahorse was sent to the Sea of Japan to map underwater minefields in preparation for a possible Allied invasion.

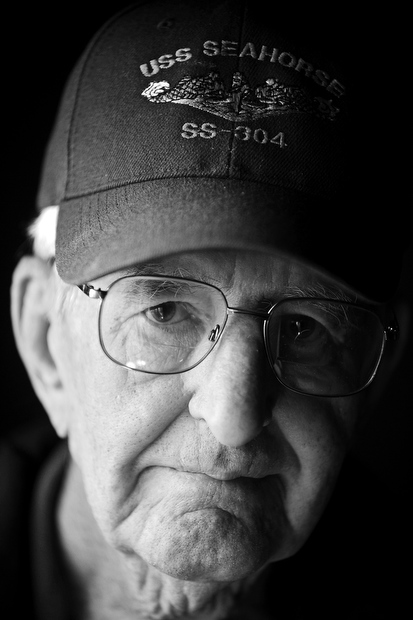

On board was Radioman 2nd Class Richard Clower. A native of North Carolina who had qualified for the Olympics as a sprinter before the war, Clower was in his third year aboard the Seahorse.

During five wartime patrols on the sub, Clower and the crew had come under attack many times. Depth charges and airplane attacks had become part of the extraordinary “normal” that comes with war.

But Clower, who now lives in a retirement community in Bozeman, said that of all the attacks, the one in the shallow waters off Japan was the scariest.

“That was the only time I could honestly say that I didn’t think we’d make it out of there,” he said.

He did make it, of course, and so did the Seahorse, which limped back to port after the attack.

Now in his 80s and retired after a career as a school administrator, Clower looks back on his time in the Navy with mixed feelings.

He enlisted in the Navy in August 1942 after studying at the University of Wisconsin’s radio school, and once he was in, Clower volunteered for the submarine service.

“Many of us who enlisted, I guess they’d say it was the thing to do,” he said. “You want to do something unusual, something different that helps other people.”

But the submarine service offered more than just adventure. During his time on the Seahorse, the sub damaged 15 enemy ships and sank 24, including a Japanese troop ship — fully loaded.

“There must have been 4,000 guys in the water, and there was no way they were going to survive,” Clower said. “They were Japanese soldiers, but we got to thinking later on that they were people, too.”

Being responsible for the deaths of thousands of people isn’t easy to reconcile, he said, and those feelings only grew stronger as the years slipped by.

Remembering that it was part of a larger effort, part of the ultimate goal of winning the war, doesn’t help much.

“You don’t think about goals; you only think about your own survival and killing the enemy,” he said. “And you don’t think about Judgement Day either. If you did, you’d go crazy.”

Thankfully, Clower said, there are plenty of other memories to go along with the combat, like the time spent in Hawaii or Australia between cruises and the friendships made with crewmates.

“The least amount of memory I have was sinking ships,” he said. “You have to remember the other things that happened.”

He still keeps in touch with his crewmates and has attended a convention with them for years, but, odds are, that won’t last much longer.

“Probably this year or the next will be the last,” he said. “There just aren’t enough left.”

Despite the sacrifices — Clower never did make it to the Olympics, though he now runs in the Senior Olympics — he remembers that it was his choice to go to war, and he can’t imagine his life going any other way.

“Every war has a unique experience,” he said. “Those people who aren’t in it will never experience it. And you never want other people to experience it, but you’re glad you did.”

Michael Becker can be reached at becker@dailychronicle.com